Slow Food: Snails and the Culinary Geology of Somerset

The surprising history of snail-eating in Somerset reminds us of the relationship between our food and the landscapes that produce it.

In our house there is a running joke around meal times. When negotiating with our two children over what is on the menu, we threaten them with offers of snail stew, slugs on toast, worm sandwiches and so on. This is met with cries of “No Daddy!!” and “Bleeurrgrrrrrr!!”, but usually achieves the aim of distraction from complaints over the actual food on offer. Occasionally, however, I catch myself wondering—usually in moments of existential dread that parents of small children are particularly prone to—whether such alternative sources of protein will one day become necessities.

Snails are thought a foreign delicacy to these lands. Perhaps not in the finer metropolitan establishments, but certainly in the average country pub. Surprisingly, however—as highlighted in a recent article in Hugh Thomas’s excellent and aptly titled Wallfish Journal (subscription required)—a dish of locally-farmed snails could be enjoyed at the Miners Arms in the Somerset village of Priddy as recently as the late 90s. The landlord and snail farmer may have been something of an eccentric character, but the consumption of snails in this part of Britain was not as anomalous as you might imagine.

March of the Roman snails

Helix pomatia, the large, edible gastropod known as the Roman snail, are abundant in the Mendip Hills, where it is believed they were introduced by the Romans during their occupation of Britain. One might imagine centurions in nearby Aquae Sulis, wolfing down a plateful after a rejuvenating dip in the thermal pools that would make the city of Bath world famous. Jump forward a few thousands years, and snails were still being served to Mendip pitmen at the Miners Arms after a shift at the ore face, a century prior to being reintroduced to the menu, albeit as something of a novelty.

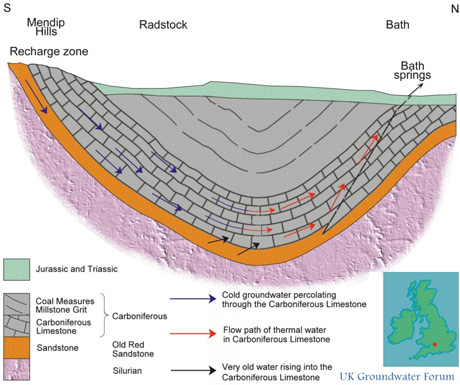

The Mendip Hills are formed of Carboniferous limestone, and here there is a fascinating reminder of the interplay between geology, water, food and culture. Limestone is a soluble and porous kind of rock that lends itself to the deposition of minerals like lead, which the Romans valued for plumbing. The thermal waters piped into the bathing pools of Aquae Sulis originate from these hills, flowing down through cavities in the rock to be heated at depth, and rising again beneath Bath.

Limestone, snails and other delicacies

Limestone’s alkalinity also supports the regeneration of snail shells, making the Mendip Hills a perfect environment for these slimy creatures. As a result, following their introduction, Helix pomatia have thrived to such an extent that—alongside the extractive industry pioneered by the Romans two millennia ago—they have endured to be embraced by the communities who made the most of what their landscape offered.

Arguably, then, snails can be added to the relatively short but venerable list of foods that you may describe as characteristic of Somerset, and which also bear relations to the geology that underlies the region. Cheddar, one of the world’s most-consumed cheeses, is said to have been lent its distinctive character by the ageing process that took place in the cool limestone caves of Cheddar Gorge. Meanwhile, the apple orchards of Somerset’s iconic cider industry have thrived in the rich, well-drained drained soils that are typical above limestone bedrock.

Culinary geology

The relationship between geology and food runs deep. The carboniferous limestone formation that forms the Mendips continues northeast, bisecting Britain until it meets the eastern borderlands between England and Scotland. Along its route are Bristol’s Avon Gorge, the Peak District and the Yorkshire Dales. Either side of this geological divide, the contrasting landscapes of southeast and northwest Britain have historically shaped distinct food cultures.

In the southeast, fertile soils and a milder climate supported grain farming, fruit orchards, and trade-driven varieties, resulting in a diet rich in bread, fresh dairy, and imported spices. Meanwhile, the northwest’s rugged terrain and cooler climate fostered pastoral farming, root vegetables, preserved meats, and foraging, creating a diet centered on mutton, cheese, and stews.

Today, however, much of this diversity and nuance is long lost to the global, supermarket-dominated food system. In the process, our sources of sustenance have become atomised, our cultures untethered from the land that sustains us.

Climate and food

Of course, snails remain well outside of the culinary mainstream in Britain. However, growing pressures on our food supply chain by the climate and ecological breakdown is already prompting some to look to unconventional sources of calories. Insects, long a staple in many cultures, are gaining attention as a sustainable protein source. Cricket flour, mealworm snacks, and grasshopper tacos are increasingly marketed as alternatives to resource-intensive livestock farming.

So, a future in which our children find snails on their plates, not only in posh restaurants but even at home, is not impossible. Given recent concerns over the impact of our shifting weather patterns on populations of pollinating insects, soil fertility and global harvests, it may even be necessary.

Slow food culture

But perhaps the case of the humble Mendip wallfish serves as a reminder to look down, as well as back, to the links between the geological and the culinary. This resonates with the growing momentum behind local and ‘slow’ food movement, which encourages people to reconnect with the supply chain and reduce the size of their foodprint. The Frome Food Network is one group behind this movement in Somerset, supporting events like This Food is Rubbish, which framed the snail (among other foodstuffs) as locally abundant but underappreciated through Cherry Truluck and Annalee Levin’s edible lecture.

To paraphrase food expert and journalist Hugh Thomas, the reason we like to have a sense of local food culture is because we fear losing a connection to the past. “A food culture offers a shared identity for people living within it—one which can and should help those people form a deeper, positive relationship with food in general”, he writes. “Eating snails is part of the story of Somerset’s past, its natural geography, and its people.” Perhaps understanding our geological heritage is another way to foster an even ‘deeper’ appreciation for the food on our plates and the landscapes that produce it.

With thanks to of , who inspired this article and encouraged me to write it.